In this armchair-philosophy blog post, I’ll argue that we need to talk about emergence with scientific detachment, and one way of doing that would be to emphasize its role in explanation rather than as a phenomenon in itself.

The eye of the beholder, after all

The wonder of life itself is the wonder of emergence. Without it, our cells would be mere lumps of chemicals; our emotions would be the featureless firings of nerve cells, and the hallmark of humanity, our language, would never have existed. As the sciences of complexity unravel the mysteries of emergence, we will finally have the key to life itself in our hands.

I made that quotation up, but there are plenty of similar paragraphs by anyone from spiritualists to academics [i]. The statement itself is not necessarily wrong, but selling complexity science by mystifying emergence and invoking some spiritual dimensions is a great disservice. It should be self-evident that such value statements lie beyond science. Think of the agent-based models (something like the figure below) explaining murmurations of starlings. Everything is there—from the birds’ behavior to the flock’s motion and density fluctuations—what more can you demand of an explanation? Well, you might say, “It surprises most people that the model would behave like that.” [ii] Such a dialogue could go forever, circling around epistemology, metaphysics, ontology, and other of your favorite philosophical topics, and be intellectually rewarding and fun. However, we should really separate philosophy and science here. Scientifically, we are trying to explain the world—no more, no less than any regression-analyzing social scientist, genome-sequencing biologist, or accelerator-swaggering physicist.

Complementing causality

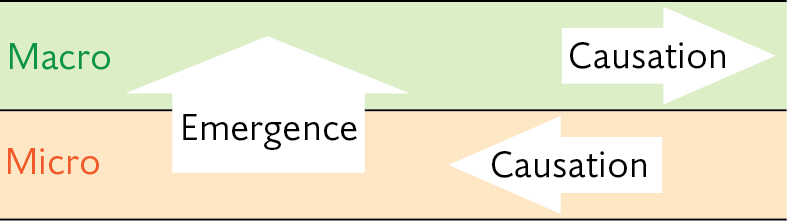

We can alleviate the above problems by presenting emergence as the scientific explanation [iii] of emergent phenomena rather than a phenomenon as such. Since explanations concern the communication of knowledge, we thus distance the phenomenon (and therefore the subjective statements) from emergence. This would also simplify the jargon—emergence would complement causality [iii]: When explaining a phenomenon within one level of abstraction, one presents causes and effects. When explaining an aggregate phenomenon in terms of a lower level of abstraction, one uses emergence. (See the figure.)

FAQ:

Q: What about the opposite of emergence? A: That is sometimes called downward causation, but usually just causation, too. But this picture is not meant to be complete—there are other forms of explanation, etc.

Q: What’s new about this? A: Not much, but a little. Read the text.

Q: To be precise, causation is not a form of explanation. A: “Skepticism is like a microscope whose magnification is constantly increased: the sharp image one begins with finally dissolves” Stanislav Lem, His Master’s Voice.

Q: How does this apply to embodied AI? A: “Does the body rule the mind, or does the mind rule the body? I don’t know.” The Smiths, Still Ill.

Try replacing “emergence” with “causality” in the above quotation. It makes the statement silly because any type of sublime profundity lies in the specific type of mechanism, not in causality as such. I wish the situation would be the same for emergence.

Hang on, you say, what about explaining non-emergent phenomena in terms of a lower level? I actually don’t think there are any such. With a reasonably generous description of emergent phenomena—e.g., “regularities of behaviour that somehow seem to transcend their own ingredients” [4]—non-emergent things would not need lower-level explanations. I expect some people would insist on a more narrow definition, but the simplifications could maybe convince them to turn this into different types of emergence (which are enthusiastically discussed anyway [5]).

Correlation is not causation, but sometimes causation is not explanation

Emphasizing emergence as a form of explanation akin to causality also solves a problem one would otherwise have—to find room for causality in explanations of emergent phenomena. Emergent phenomena inevitably contain causal feedback loops that make an explanation in terms of cause-and-effect relationships hard to interpret (in addition to being notoriously hard to detangle observationally). Since such explanations inevitably need to be different than usual, it would be great with a word unifying them.

Now the discussion is slowly drifting toward “systems thinking”—another buzz-concept of yesteryear also emphasizing that complex systems need unorthodox scientific explanations. Systems thinking also covered a vast expanse of quasi-philosophical ground, from dry systems-dynamics simulations to new-age spirituality. … but that’s a story for another day.

A historical digression

In the early complexity science literature, emergence was relatively rarely discussed as a general phenomenon, and thus closer in spirit to my proposal. Authors talked about “the emergence of complexity” [6], “the emergence of metabolism,” [7], etc., not just “emergence.” However, something happened around that time. Maybe it was just that people were using the word so much that it seemed like a buzzword needing attention per se. [iv] Maybe John Holland’s book Emergence [3] had some impact in touting its eponymous concept as self-contained and well-defined.

A third factor affecting the usage (and, consequently, meaning) of “emergence” was probably the increasing interest of physicists. At the time, statistical physicists took note of the now buzzword and rightfully felt that “hey, we’ve been studying emergence like forever.” The problem was that emergence in physics was typically not described in very general terms. To the rescue, they discovered Philip Anderson’s by then 20-year-old article “More is different” [v]. In this paper, Anderson showcased several phenomena where many (“many” now meaning “many enough for infinity to be a reasonable approximation”) interacting agents show qualitatively new behavior as a whole.

This stronger influence of statistical physics has somewhat shifted the meaning of “emergence” away from describing a dynamic scenario with a clear before and after (“the emergence of life on Earth”) in favor of the statistical physics” focus on the conditions for the state of qualitative difference to happen at all. Another consequence is that authors influenced by physics would not associate the Gestalt psych style “different from the sum of its parts” with “emergence” since their number of parts is too small to matter in statistical physics.

In sum, I wish we could rewind to the early 1990s and take a different path from there.

Final thoughts

This blog post is all about finding a way to use words that is efficient, precise, and helpful for scientific discovery. This will also help anyone who seriously wants to explore other aspects, religious or not.

Sometimes I feel that scientists (myself included) don’t spend enough effort revising our language. We don’t get much help from office-chair philosophers either, who typically are somewhere else in space and time, ostensibly battling against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.

More often, I feel that scientists spend too much time on meta-discussions, which are little more than thinking out loud about something well-known to many (like this blog post). We will always be hostages to the limitations of language, but that shouldn’t have to stop a scientist. I should roll up my sleeves and get back to work.

Notes

[i] I should make a collection of such quotations, but in the meanwhile, see Refs. [1], [2], and tweets like this (that prompted me to write this blog post).

[ii] The title of this section alludes to John Holland’s book Emergence [3] where he mentions that surprise is a crucial element of emergence and that it doesn’t go away even though you’ve been able to model it. So, in that sense, emergence is not an “eye-of-the-beholder phenomenon.” I’m not sure if I agree. Now that I’ve seen bird-flock models, I would be surprised if any similar model doesn’t do something similar. But that is not the point here—the point is that we shouldn’t present emergence together with our feelings and subjective values.

[iii] I allow myself to be a bit simplistic about the meaning of “explanation.” Identifying causes and effects is, technically speaking, part of one mode of scientific explanation. Being sloppy like this is my self-granted armchair privilege. 😛

[iv] If there is a common word, people tend to think it must correspond to something meaningful in reality. (What is a good reference for this? I’m sure there’s a good one, but I forgot.)

[v] “More is different” [8] was a remarkably late bloomer citation-wise. According to Google Scholar, with 116 citations during its first decade and only a handful coming from physics. During its second decade, it gathered a mere 79 citations, also very few from physics (Ref. [9] being a notable exception). This is remarkable since, during this time, physicists were getting into complexity science via self-organized criticality and traffic-flow models. Then 311 citations during decade three, and still (!) remarkably few statistical physics papers. From 2003 to 2012, however, there were 1360 citations, and interdisciplinary statistical physicists contributed with a majority. The fifth and latest decade has continued the exponential (?) growth with 3650 additional citations.

References

- Adyahanzi, BG Dempsey, 2022. Emergentism: A Religion of Complexity for the Metamodern World. Metamodern Spirituality.

- R Larter, 2021. Spiritual Insights From The New Science: Complex Systems And Life. World Scientific, Singapore.

- JH Holland, 1998. Emergence: From Chaos to Order. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- J Urry, 2012. Global Complexity. Polity, Cambridge.

- MA Bedau, 1997. Weak emergence. In J Tomberlin, ed., Philosophical Perspectives: Mind, Causation, and World 11. Blackwell, Malden, 375–399.

- P Bak, K Chen, M Creutz, 1989. Self-organized criticality in the Game of Life. Nature 342, 780–782.

- RJ Bagley, JD Farmer, 1990. Spontaneous emergence of a metabolism. Artificial Life, Santa Fe.

- PW Anderson, 1972. More is different. Science 177, 393–396.

- H Soodak, A Iberall, 1978. Homeokinetics: A physical science for complex systems. Science 201, 579–582.

Great article! There are indeed scientific explanations for emergence and no need to revert to mysticism. Take catalysts for example. They rely on their molecule being a particular shape and that shape is of course not a feature of the component atoms. On a separate subject, vanishing properties seems to be a good term for the opposite of emergent properties.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I meant opposite in the sense that a phenomenon at a lower level of description is explained by a phenomenon at a higher level. Like an individual bird flew in a particular direction because its flock did.

LikeLike

Thanks Petter, apologies for getting that wrong. Your article is very thought provoking. Regarding birds, as you know Prof. Parisi has modelled their murmurations and his papers can be downloaded from Academia. Their behaviour is important because it is reflected in human society and seems to be a form of positive feedback. Individual behaviour causes social behavour which causes individual behaviour. As I undertand it starlings behave in that way in the evening. It leads to them roost in flocks thus providing safety for individuals from predators. So, there is an evolutionary explanation for their behaviour and the two properties, individual behaviour and crowd behaviour have almost certainly co-evolved. Getting back to their flight patterns, the thing I find interesting is the way that they turn and gyre. Pure feedback would cause them to fly perpetually in the same direction. Also, why do subgroups break off and then rejoin? This too is reflected in human society. Any thoughts?

LikeLiked by 1 person

One thought is that there is an entire field of collective animal behavior (see, e.g., https://www.ab.mpg.de/couzin ) that studies both emergent phenomena and evolutionary forces. Another thought is that I’m not a big fan of applying evolutionary ideas to modern humans (modern enough for economic success and genetic survival to be decoupled). There is a field exploring such ideas https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169534700020772 but I think that is pushing the analogy way beyond its area of validity, but that’s a longer story.

LikeLike

A challenging essay; well done!

I got here more or less by emergence from a reference, and I cannot say that I am much the better for it — yet. I certainly realise from my reading here, that my views to date have been simplistic, and I have a growing suspicion that concepts of emergence confuse and conflate separate and distinct entities or concepts, or invalidly distinguish essentially identical essences, but I am struggling to envisage, classify, and justify them.I grit my teeth and thank you, but cannot claim that the experience is comfortable…Wish me luck.

LikeLike