When we learn things by studying or doing research, we perceive understanding as coming to us in step-like a-ha moments.1 I will argue that these moments happen more likely when we recognize (or map our observations to) specific patterns of explanation. The snag is, of course, that reality doesn’t always follow human-preferred patterns, so they can lure us away from a more accurate and comprehensive understanding.2 Earlier posts have covered direct analogies and symmetric theories. Now we turn to explanation by optimization. (The background picture is based on the cover art for JP Sartre’s The Psychology of Imagination.)

Counting words

In the final year of the 1940s, maverick Harvard linguist George Kingsley Zipf published Human Behaviour and the Principle of Least Effort, where he argued that statistical properties of language, like its power-law word-frequency distribution, result from humans optimizing the efficiency of their language. Zipf didn’t make this argument in the form of a mathematical theory, but since the Principle of Least Effort became an almost instant scholarly hit, no wonder a young mathematician, Benoit Mandelbrot, soon reformulated Zipf’s arguments into equations [6]. Yet a few years onward, another legend of the game, Herbert Simon, published a profoundly different model for similar distributions. Simon didn’t presume any underlying purposes or intentions; instead, his model assumes a constrained form of stochastic growth [7]. Despite their models representing different forms of scientific explanation, Mandelbrot and Simon clashed in a monumental exchange of commentary articles that, later in their careers, must have been somewhat embarrassing—both failing to see the big picture while eager to discuss technicalities.3

Today, many more models of the emergence of the statistical properties of text have been proposed. Many pathological wrinkles of Mandelbrot’s and Simon’s models have been ironed out. However, the basic classes of models—optimization vs. constrained evolution—remain4, as does the explanatory tension between them: there are undeniable optimization processes at work (like common words being shorter). These processes affect the word frequency distribution. At the same time, at a micro level, it is no more than a relatively weak correlation, far from the astounding accuracy of Zipf’s law. Thus, there must be some blind statistical smoothing at work as well. In sum, Zipf’s law is an example of how the successful linking of a micro-level optimization principle to a macroscopic phenomenon still makes for only a ramshackle theory.

Rationalizing rational choice

In the social sciences, the standard criticism of explaining by optimization is simply that people don’t usually optimize. Jon Elster, nestor of rational choice theory, wrote this in the introduction to an edited volume on the topic: “Many actions are performed out of habit, tradition, custom or duty—either as a deliberate act to meet the expectations of other people and to conform to one’s own self-image, or as the unthinking acting-out of what one is.” [11] I agree entirely, and it is not an argument we can shoo away. I mean, I’m being philosophical now, and I love digging into the arguments, but this is obviously when we should science an answer—what point is there to be philosophical about a truth that is just out there to measure?

Ah, let’s philosophize just a little bit more about rational choice because it really illustrates the point of this post—the exceptionalism around explaining behavior as optimization. Part of my research aims to understand prosociality—the tendency for people to choose cooperation over selfish short-term gains. This is a grand research theme that has drifted in and out of disciplines in a fairly unique way, and typically presents itself as exceptionally versatile. It can bring us understanding of “the myriads of human interactions that take place every day in families, neighborhoods, markets, organizations, or the political sphere” [12]. So unlike Zipf’s law above, this field is not restricted to statistics but also a self-proclaimed framework for analyzing individual decisions.

Now, if I think of a concrete prosocial decision I recently made—to be a mentor for a young faculty member of another university.

– Was it to get favors in the future?

– Not at all.

– Was it to sharpen your CV?

– Come on!

– Was it to level up my reputation among my colleagues?

– Seriously? No!

– Tell me then.

– Well, maybe some “unthinking acting-out of what I am,” plus that the question came at a moment I didn’t feel so overburdened.

This little interview could be seen as a complete explanation of my behavior, but please allow me to simulate a response by a hypothetical mainstreamer who would not stop until they had identified an optimization mechanism. They could maybe reason:

– OK. It may not be reputation in your case, but your “unthinking acting-out of what you are” is just you following a norm that has evolved to ensure that people keep a reasonable balance between their commitments.

Let’s pause now to read the situation above closely and critically. The mainstreamer has now shifted the perspective to something much vaguer (norms and cultural evolution), on a different timescale (years rather than seconds), incomplete (there are many other similar rationalizations), etc., all because of the allure of explaining something as optimization.

There are more low-key ways of rationalizing my behavior—maybe “Your social preferences make you feel that your workload does not balance out the guilt you would feel if you said no” [12]. But also those would introduce an almost insurmountable amount of complications since we would have to tease them apart from hundreds of imaginable mechanistic explanations at the same level of abstraction. So understanding concrete situations—like, for example, most things of interest to decision-makers—cannot take the form of identifying an optimization process. Yet that is precisely what people do, because, by human nature, it just gives a so much stronger sense of understanding compared to other mental models of the situation.

Spandrels and levels of explanation

In the theory of evolution, the question of explanation by optimization is more tangible than in linguistics or the social sciences [13]. Today, few people would present natural selection as simply optimization. This insight, dating back to Darwin himself, was famously and eloquently argued in Steven Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin’s 1979 essay “The spandrels of San Marco” [14]. The spandrels are bent triangles between the arches, close to the ceiling of a church. They appear by necessity of the arches needed to lift the ceiling high, but are in Venice’s San Marco cathedral so sublimely decorated with Biblical narratives that one may get the impression that they are the purpose of the building and the rest of the church there to their support. By this5 analogy, Gould and Lewontin went on arguing how traits not only evolve further if they are already good enough for an organism, they are also often the result of other evolutionary pressures than their current function suggests. Gould and Lewontin’s targets were the so-called adaptationists who discussed evolution in terms of the independent optimization of each trait for its current function.

The cases of mismodeling above could maybe have been alleviated if scientists put more soul into thinking about levels of explanation. Maybe to little surprise (given, inter alia, the spandrels paper), this awareness seems most advanced in biology. Such discussions have taken the edge off optimization exceptionalism in favor of more deliberate epistemic categories like Niko Tinbergen’s four levels of questions [15], or Rupert Riedl’s hierarchy of explanation [16].

Wannabe variational principles

It would be hard to claim the eureka fallacy of optimization to come from a universal human instinct if we didn’t see it in physics and chemistry as well. But oh yes, we do.

Variational principles are ways of casting fundamental physics problems into optimization ones, which one can then solve by the calculus of variations. Hamilton’s principle is an equivalent reformulation of Newtonian mechanics. Fermat’s principle in optics follows from Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism. But then there is an entire bunch of non-nomological variational “principles.” A full spectrum, from “provable in special cases” to “imagine it was actually true.” I won’t go into specifics now (maybe in another post), but things of the format “the maximum/minimum entropy/free energy/information (production) principle.”6 For all of these, devout believers have to learn to deal with situations when reality deceives them [18]: – “It gives a general direction. It is not meant to be taken too literally in specific situations.” – “Why don’t you call it a hypothesis then, if that’s what it is? ‘Principle’ makes it sound like a physical law, which it isn’t, no matter how much you wish for it.” Etc.

I’m not saying that optimization will not be a part of the ultimate formulation of the physics and chemistry of our environment. If optimization had nothing to say about the pattern formation of flow systems (river basins, lightnings, etc.) [19], then I’m outta here. But we have to find a different way of talking about such “principles” that come with limits and caveats than just branding them (and pretending they are) universal. It’s sometimes too easy to poke fun at physicists’ Newton complex, missing the truth in front of their eyes, because they’re just seeking universal laws. But that’s a different litany. Now the point is that the burden of proof for variational principles is lighter because they tap into the human fondness for explanation by optimization.

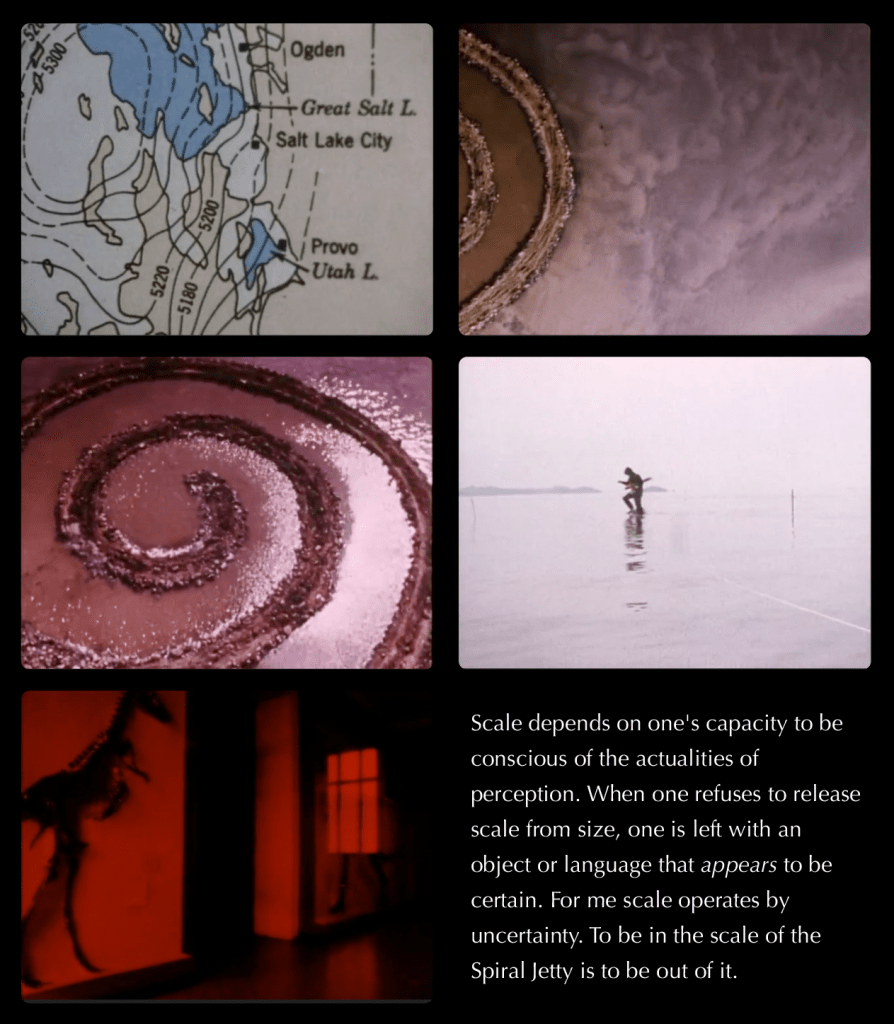

I’ve recently been into Robert Smithson’s art and writings. Here are some stills of his film Spiral Jetty (1970), documenting his most famous earth-art piece Spiral Jetty, and a quotation from his essay about it (entitled: Spiral Jetty [17]). Is it related to the rest of this post, and if so, how? I leave that for you to ponder upon.

Executive summary and manifesto

In “The spandrels of San Marco,” Gould and Lewontin blamed laziness and habit for the adaptationists’ inability to break free from iterating their misconceptions. I really think all this is much deeper than academia. From toddlerhood onward, through school and professional careers, we are continuously trained to explain things as a result of working towards a goal or realizing a purpose. This is not always the same as explaining by optimization, but even if it isn’t, it is compatible.

In general, our sense of understanding is, to a large degree, a social construct, trained by repeated exposure to explanatory patterns.7 In science and social science, it, of course, makes sense to present others with explanations following similar patterns, because making them go “a-ha!” is the goal here. This, in turn, gives more exposure to the patterns. Patterns that do not always transfer the best possible knowledge. We tend to see optimization because we’re looking for it, not because it is there. It’s not always wrong to explain phenomena as optimization, but if you do, you have to show that optimization is happening, not just explain the phenomena under the assumption that there is optimization.

Notes

- The psychology and philosophy of the sensation of understanding is a wide and fascinating topic that I can’t claim to be an expert on. (But that has never stopped me from writing about it, has it? 😜) The literature discusses more cognitive reasons for the sense of understanding [1] and more social ones [2]. From what I can tell, it all seems fairly consistent with my analysis. ↩︎

- The nature of understanding and the gap between understanding and the sense of understanding are, of course, also often-discussed topics. Wittgenstein’s “now I can go on” argument (that understanding is what you do when acting out that understanding in a way acceptable to others [3]) applies in this context; as does Rozenblit and Keil’s work on the overconfidence in one’s ability to explain complex phenomena [4]. Burton’s On Being Certain is a pop-science book on the topic that I just browsed through quickly [5]. ↩︎

- They published a total of six commentary articles in the journal Information and Control, ending with [8]. ↩︎

- See [9] for a contemporary model in the vein of Zipf and [10] for a more Simonesque version. ↩︎

- I haven’t been to that cathedral, but I’m a bit skeptical that people would not think of it’s spandrels as an epiphenomenon, regardless of their decoration. Anyway, it’s funny how evolution evokes colorful analogies, blind watch makers, Swedish kebab pizza (that my colleague used to explain horizontal gene transfer, as such pizza not only contains kebab meat, but also the same garlic sauce as proper kebab), dancing fitness landscapes, etc. ↩︎

- A bit sarcastically, but still: If any of these combinations don’t exist, one could probably claim it. Entropy is a Manichean devil, as Robert Smithson put it—an enemy of the good that isn’t obviously evil [17]. ↩︎

- Social processes influence science more conspicuously at a collective level. This post focuses on what happens in an individual, but that is, of course, connected to the social construction of scientific facts [20]. ↩︎

References

- A Koriat, 2000. The feeling of knowing: Some metatheoretical implications for consciousness and control. Conscious Cogn 9:149–171.

- LV Vygotsky, 1978. Mind in Society. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

- L Wittgenstein, 1972. Philosophical Investigations. Basil, Oxford, §§151.

- L Rozenblit, F Keil, 2002. The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth. Cogn Sci 26:521–562.

- RA Burton, 2009. On Being Certain. St. Martin’s, New York.

- B Mandelbrot, 1953. “An informational theory of the statistical structure of languages” in Communication Theory, ed. W. Jackson, Butterworths: Oxford, 486–502.

- HA Simon, 1955. On a class of skewed distribution functions. Biometrika 42:425–440.

- HA Simon, 1961. Reply to Dr. Mandelbrot’s post scriptum. Inf Control 4:305–308.

- R Ferrer-i-Cancho, MS Vitevitch, 2018. The origins of Zipf’s meaning-frequency law. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 69:1369–1379.

- SK Baek, S Bernhardsson, P Minnhagen, 2011. Zipf’s law unzipped. New J Phys 13:043004.

- J Elster ed, 1986. Rational Choice. New York University Press, New York.

- E Fehr, G Charness, 2025. Social preferences: Fundamental characteristics and economic consequences. J Econ Litt 63:440–514.

- J Monod, 1971. Chance and Necessity. Random House, New York.

- SJ Gould, RC Lewontin, 1979. The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: A critique of the adaptationist programme. Proc R Soc B 205:581–598.

- SA MacDougall-Shackleton, 2011. The levels of analysis revisited. Phil Trans R Soc B. 366:2076–2085.

- R Riedl, 2019. Structures of Complexity, Springer, Cham.

- J Flam, 1996. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. University of California Press: Berkeley.

- AH Reis, 2014. Use and validity of principles of extremum of entropy production in the study of complex systems. Ann Phys 346:22–27.

- A Bejan, S Lorente, 2010. The constructal law of design and evolution in nature. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 365:1335–1347.

- B Latour, S Woolgar, 1979. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Sage, Beverly Hills.