This post continues the theme of how quirks of the human psyche limit our advancement of knowledge1—quirks that are very much avoidable if you are aware of them, but if you aren’t, they move the goalposts for scoring that Eureka feeling. I’ll entertain the hypothesis that if we are presented with a symmetrical, neatly structured theory, we could go: “Oh yeah! makes sense,” when we really should have pushed the bullshit button.2

Don’t get me wrong, searching for symmetry and neatness has been a driving force behind an incredible amount of human intellectual achievement—from the Pythagoreans to Murray Gell-Mann. But given our fondness for symmetries, I’m beginning to think that the success rate of symmetry-based ideas may not be that great after all—the denominator must be a substantial fraction of all ideas we ever got.3

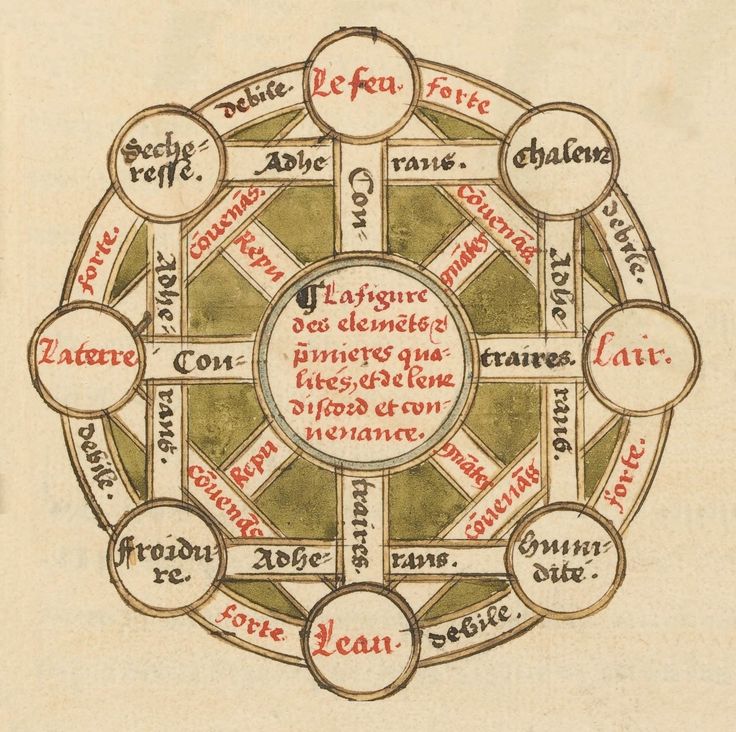

One realm where symmetric relations or division between concepts is uncontested is religion and spirituality. From hierarchies of angels, to the Kabbalistic tree of life, to the mandalas of Vajrayana Buddhism, to the principles of Theosophy. Furthermore, check your alchemy cookbook, witchcraft manual, or astrology chart—there will be symmetric diagrams all over.

Fast-forward to the last century of applied social and behavioral science4 and lo and behold: Zachman 6×6 Framework for Enterprise Architecture, McKinsey’s 7S Schema to analyze the structural organization of firms, The Burke-Litwin model of organizational change, Galbraith Star model, Porter’s diamond, Freud & Jung’s psyche maps, Talcott Parsons’ AGIL paradigm, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Dale’s pyramid of learning, etc., etc. These cases represent a complex reality shoehorned into a symmetric form. But, hey, you say: This is exactly what theorizing is—communicating insights to people. We humans, with the Gestalt principle of symmetry hardwired5 into our brains, have an easier time accepting and assimilating symmetric theories. Theories have to be biased toward symmetry, or else they simply have to be shallower.

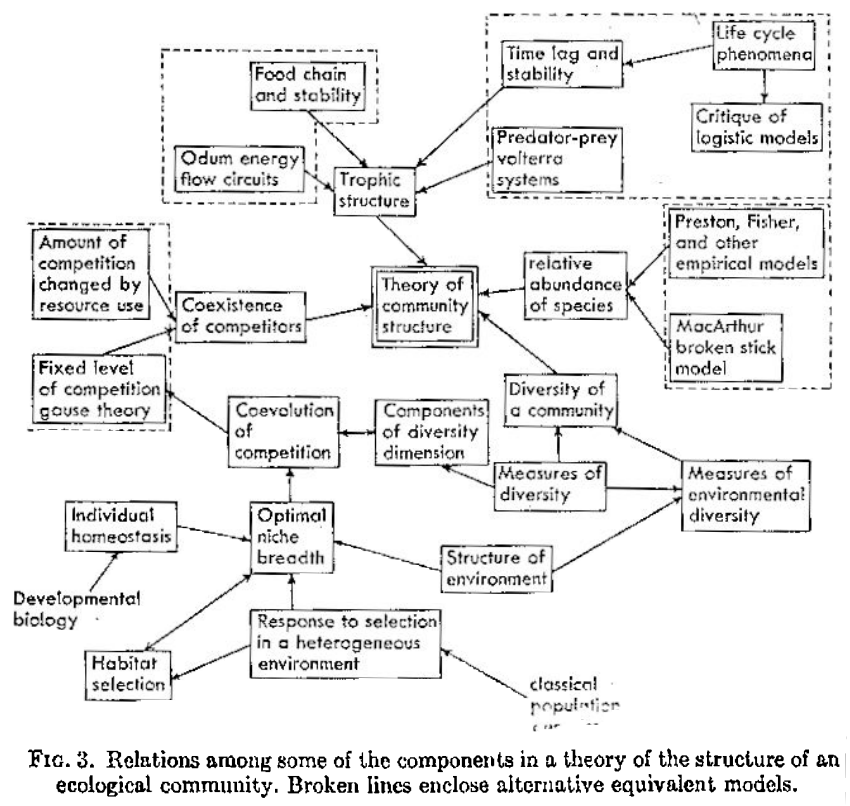

However, the (more aggravating) flip side is that theories expressed by symmetrical arrangements of concepts and dependencies are, typically, further from the truth than messier theories. Representations of reality built without explicit care for symmetry and order do exist and are perfectly understandable (see below). It would be much better if the veracity of science were decoupled from its graphical representations. Now, when I review grant applications where the program “naturally falls into” four work packages, each divisible into three subtasks that take an equal number of collaborators and Gantt-chart space, it feels just too far from any realistic actual project (even if a realistic-looking research project would not necessarily be closer to an actual, future course).

And, by the way, there is new science on this—or at least a closely related—matter. A recent Nature Communications paper found that “decision-makers, intending to maximize profit, may be lured by the existence of regularity, even when it does not confer any additional value.”

Footnotes

- For other such posts, see here, here, and here. ↩︎

- I can’t find my copy of Bergstrom & West’s book. I don’t recall that they had symmetry as an example of a smoking gun, but they should. ↩︎

- The paramount example here, both in terms of the amount of invocation of symmetry and thought hours per validated insight, is, of course, superstring theory. ↩︎

- I guess management and organizational studies are notorious, but as the examples show, they are not the only branches with such theories and models. ↩︎

- There is even a selfish-gene-style teleological explanation for that: More symmetric bodies have had fewer developmental problems, would thus maximize the offspring’s fitness, and would therefore be more desirable to reproduce with. ↩︎

The cover picture contains a tree of life from Pinterest, the McKinesy 7S model from here, some theosophy diagrams from here, The Burke-Litwin model from here, a figure from Athanasius Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis, and Galbraith’s star model from here.

It reminds me of a piece titled Conversation with the Master by Shorab Sepehri, an Iranian painter and poet; A philosophical reflection on symmetry in art, architecture, and nature, framed as a dialogue between a former student and a French professor. It contrasts Eastern and Western aesthetics, where the East embraces symbolic, spiritual symmetry and values imperfection, while the West emphasizes rational composition, realism, and perspective. The text defends traditional Persian and Eastern art as intuitive, contemplative, and unified, criticizing Western art’s focus on technique, illusion, and dominance of the viewer’s gaze. It’s ultimately a meditation on how form reflects worldview.

You can find the text in Persian here:

https://sohrabsepehri.org/prose/books/goftogou-ba-ostad/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment Abbas! I should check out that book.

I think there is plenty of appreciation of symmetry in Eastern cultural expressions and thinking from Islamic art, via Buddhist mandalas, to yin-yang symbolism and 八卦 ba gua. Maybe the West has been a bit late to appreciate spontaneity, fluidity, and imbalance; and maybe the West only discovered it because of the East, but still, I think the East-West dichotomy isn’t overly helpful and more importantly: people all over the world have discovered that the beauty in symmetry is not the end of the story.

As an example of distinctively Western stuff, yet with Eastern aesthetic values, I’m a big fan of the graphic designer Alexey Brodovitch.

LikeLike